Ever since Pierre Proudhon’s ‘Dialogue With a Philistine’ in ‘What is Property’, in which he became the first political philosopher to declare himself, ‘(in the full force of the term) an anarchist’, anarchism has flourished into a self-aware ideology and political movement that has had a profound influence on the broader workers’ movement and the class struggles of the last two centuries. Anarchist theory has developed over time and can now be categorised and sub-categorised into a multitude of theoretical variants, all of which share a common incredulity towards central government and the state. The classical anarchism that inspired the anarchist revolutions in Catalonia during the Spanish Civil War, as well as the anti-statist communism spread by Nestor Makhno’s Black Army in Ukraine after the Russian Revolution has evolved rapidly since the end of WWII, with changes in theory and praxis corresponding directly with changes in the nature and ethos of capitalism itself, in the transformation of power relationships and in the changing role of the state in modern times. Anarchist discourse has adapted to the fluctuations of global capital. From the stages of early industrialisation and classical liberalism through to Keynesian social democracy and Friedmanite neo-liberalism, anarchism has refined its concepts and methods and continues to play a crucial role in today’s New Social Movements and extra-parliamentary, direct action political campaigns. Post-1945 anarchist thought has been influenced heavily by other strands of philosophy and social critique including post-structuralism, post-modernism, radical feminism, environmentalism and ecology, autonomism, post-leftism, ‘situationism’ and the neo-Marxism of the Frankfurt school, all of which have their own critiques of bourgeois society and have helped alter the focus and establish new trends in anarchist theory, making modern anarchism markedly different from its classical intellectual predecessor.

To begin to understand the difference between classical anarchism and post-1945 anarchism, it is essential to have a historical overview of the origins of classical anarchist thought and the class struggles and workers movements that were galvanised by its proponents. Classical anarchism emerged out of the traditions of secular Enlightenment thought, drawing on the political and moral philosophy of Jean-Jacques Rousseau and its heavy focus on notions of freedom, justice, equality and a utopian vision of the ‘general will’ expressed through the sovereignty of people’s assemblies under direct rather than representative democracy. Some post-1945 strands of anarchist philosophy, under the influence of thinkers such as Michel Foucault, have challenged the philosophy of the Enlightenment and the universalities and essentialisms it arouses, particularly the essentialist tenets espoused by some classical anarchists. Just as it is today, with the mainstream press pouring fervent disdain and condemnation on the ‘thuggish and mindless’ tactics of ‘Black Bloc’ anarchists, anarchism since its inception has frequently been dismissed as a juvenile and utopian movement, synonymous with chaos, violence and disorder. During the English Civil War, the word ‘anarchist’ was used by Royalists as a term of derision against Parliamentarians in the New Model Army. Over a century later, the term was used positively by Enragés and sans-culottes in the French Revolution to distance themselves from the post-revolutionary centralisation of power instituted by the Jacobins. However, despite having entering into the political vernacular, anarchism had not at that time emerged as a separate ideology and was yet to define itself as a distinct political philosophy. Peter Kropotkin, in his Encyclopedia Britannica entry for ‘Anarchism’ outlines the historical development and evolution of anarchist thought, tracing it back as early as 430 B.C. in the writings of Aristippus, who, ‘taught that the wise men must not give up their liberty to the State, and in reply to a question by Socrates he said that he did not desire to belong either to the governing or the governed class.’ Kropotkin thereby draws a historical and philosophical link between his own philosophical contributions and writings from several millennia past, establishing a grand ‘meta-narrative’ and ideological framework that is ‘steeped in centuries of tradition’ – this is a position and intellectual pitfall that proponents of modern post-structuralist anarchism (or post-anarchism) would take issue with. Kropotkin also accredits quasi-religious Eastern Taoist philosophy as being an early example of unconsciously-anarchist teaching. According to Kropotkin, the beginnings of anarchism as a self-aware branch of political philosophy lay in the works of William Godwin, who in his Enquiry Concerning Political Justice, ‘was the first to formulate the political and economic conceptions of anarchism, even though he did not give that name to the ideas developed in his remarkable work.’ It was Proudhon who later ascribed the term ‘anarchist’ to the ideas and concepts espoused by Godwin, planting the seeds for the birth of the mass movement and mature political philosophy.

The working-class movements of the 19th century were often dominated by anarchists, but their growth was stunted and support waned after the revolution in Russia provided leftist revolutionaries with a bastion of ‘actually existing socialism’ and ‘workers’ power’ which had the potential – and outward veneer – of physically embodying their abstract political desires. The Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm comments that although, ‘in the generation after 1917, Bolshevism absorbed all other social-revolutionary traditions, or pushed them on to the margin of radical movements… Before 1914 anarchism had been far more of a driving ideology of revolutionary activists than Marxism over large parts of the world.’ Classical anarchists and Marxist revolutionaries have never seen eye to eye. Despite their mutual enthusiasm for the overthrow of capitalism and shared longing for a workers’ revolt, their quarrels lay in their differing conceptions of society after the revolution and widely varying views on how best to bring about this revolution. The anarchists dismissed parliamentary activity as a capitulation to bourgeois political institutions, and lambasted the socialist ‘transitional phase’ expounded by Marx, ridiculing the naivety of the assertion that the state would – after a period of proletarian government and the suppression of bourgeois forces – simply ‘wither away’. The early years of the International Workingmen’s Association (IWA) were characterised by infighting and splits between adherents to statist socialism and libertarian collectivist factions centred around Mikhail Bakunin. Anarchists distanced themselves from the authoritarian tendencies of Marxism, opposing any centralised ‘dictatorship of the proletariat.’ Marxists in the International accused them of being ‘utopians’ and later, ‘petty-bourgeois individualists’ with ‘an infantile disorder’- initiating a division between statist and non-statist sections of the revolutionary left that last until this day. Bakunin, an influential figure in classical anarchist philosophy, pointed out the fallacy of any hypothetical parliamentary road to socialism, stressing the contemptuousness of vanguards lead by, ‘pseudo-revolutionary minorities’ and hierarchically-structured political parties claiming to represent the interest of the masses. He launched devastating indictments of the Marxist analysis and strategy for change, writing that for them, ‘only a dictatorship—their dictatorship, of course—can create the will of the people, while our answer to this is: No dictatorship can have any other aim but that of self-perpetuation, and it can beget only slavery in the people tolerating it; freedom can be created only by freedom, that is, by a universal rebellion on the part of the people and free organization of the toiling masses from the bottom up.’ But classical anarchism did not just exist as a negative critique of Marxism, social-democracy or state socialism. Anarchists affirmed radical libertarian values that rejected all governmental authority, calling for the complete abolition of the state, its armed wings of the police and army and its centralised bureaucratic institutions. Power would be completely decentralised and absolute sovereignty was to lie with federated workers’ councils and neighbourhood assemblies, bypassing the mediating representative power sought by parties of left and right and instituting direct democracy. The unbridgeable gap between classical anarchist and Marxist thought has continued until present day, as modern anarchists frequently assert their opposition to today’s Trotskyist and old-style Stalinist parties of the ‘revolutionary left’, providing a direct action alternative to their party political strategies, which all too often involve a re-hash of the old Leninist tactics of party-building, focusing entirely on a quantitative growth in membership, selling newspapers or ‘the party organs’ and unsuccessful electioneering.

The First International was the first manifestation of classical anarchism as a fully-developed social movement. It would later have a profound influence in the Spanish Civil War, as the grassroots membership of the horizontally-structured anarcho-syndicalist unions, the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT) and Federación Anarquista Ibérica took over industries, workplaces and the distribution of goods and services in Barcelona and rural towns across Spain, ‘wherein the means of production are commonly owned and managed by those who work them, where everyone willing to produce has free access to them, and where the means of production are monopolised neither by the private Capitalist nor by the government.’ The Paris Commune of 1871 provided the first living vision of a participatory democracy, and for Marx, ‘the political form at last discovered… to work out the economical emancipation of labour’ that anarchists, Marxists and socialists would attempt to appropriate as part of their own movements and histories, either as the first example of the ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’ or as an early archetype of a spontaneously-organised and organic federation of workers’ councils. The Commune set a precedent for all the successive revolutions, existing without a top-down command structure instituted by a political party and confirming the classical anarchists’ hypothesis that ‘transitional phases’ and revolutionary governments were unnecessary and undesirable. The Commune certainly fits more neatly into the classical anarchist paradigm for social change than the Marxist one, and Marx would later criticise the Commune for its lack of centralized organization and forced conscription, which led to the definitive Statist-Libertarian split in the Hague congress of the IWA. Participants in the Commune acted independently of any bureaucratic state institution, organising autonomously and immediately disbanding the existing state apparatus. The Commune did not collapse because of its own internal contradictions – like the Spanish Revolution, it was defeated by external reactionary forces, but its living example was an affirmation of classical anarchist values.

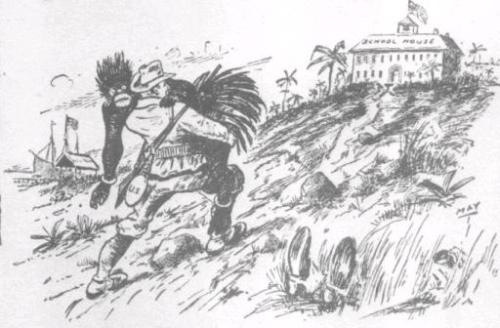

From its inception the anarchist movement has faced intense persecution and state repression. Even in the newly established ‘workers’ states’, the anarchist enclaves of the Free Territory of Ukraine were quashed by the Bolshevik Red Army after 1917. In Western Europe, a wave of terrorist bombings and assassinations inspired by Bakunin’s ‘propaganda of the deed’ led to mass arrests as anarchism in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries became ‘the enemy within’ bourgeois democracies. Echoes of this repression in the twenty-first century are obvious, as both liberal and authoritarian governments keep activists under constant surveillance, gathering intelligence on protestors and infiltrating anarchist groups with agent provocateurs to quash any serious threat to the status quo. In 1894, the anarchist Vaillant exploded a bomb in the Paris Chamber of Deputies. Before receiving his verdict he delivered an eloquent vindication of his actions that was later quoted by Emma Goldman in her work, The Psychology of Political Violence: ‘Gentlemen, in a few minutes you are to deal your blow, but in receiving your verdict I shall have at least the satisfaction of having wounded the existing society… I carried this bomb to those who are primarily responsible for social misery… Hail to him who labors, by no matter what means, for (societies’) transformation!’ The tactics of insurrectionalist terrorism carried out by some anarchists were not adopted nor supported by the movement homogenously, and some condemned them with the same vigour as the ruling classes. Anarcho-pacifists such as Leo Tolstoy were quick to denounce acts of violence on the basis that the very essence of anarchism, the abolition of force and coercion, was compromised and contradicted by its use. Tolstoy even went as far as to reject the idea of revolution and imagined anarchism as a far more personal process of inner change and moral rejuvenation. ‘The Anarchists are right in everything; in the negation of the existing order… They are mistaken only in thinking that Anarchy can be instituted by a revolution… There can be only one permanent revolution—a moral one: the regeneration of the inner man.’ The Indian independence leader, Mohandas Gandhi described Tolstoy as, ‘the greatest apostle of non-violence that the present age has produced’ and Tolstoy’s writings would later have a huge influence on successive generations of activists adopting tactics of civil disobedience and nonviolent resistance against the state and capital.

Internal ideological battles and disagreements over tactics and strategy, not least the recurring arguments over violence, have ensured that post-1945 anarchism, as much as classical anarchism, is not a cohesive, uniform movement, but a heterogeneous amalgamation of groups with differing views on how to challenge capitalism and build viable alternatives to it. The events of the last century have only served to exacerbate the sectarian tensions and division between the various stripes of anarchists. The classical anarchism of Godwin, Proudhon, Bakunin, Kropotkin and others was borne of a time of early industrialisation and laissez-faire capitalism, and anarchism’s theoretical and practical focus has developed in concurrence with developments in industrial capitalism since the era of economic liberalism inspired by Adam Smith. The Great Depression of 1929 (and some say the geopolitical influence of the Soviet Union) led to the adoption of more interventionist social-democratic economic policies that represented a tacit concessionary compromise of the bourgeoisie with the demands of the workers’ movement. After the Second World War, Keynesian economic models were adopted by liberal-democratic capitalist governments as the ‘Washington consensus’ guaranteed that centre-left and centre-right governments alike would provide a minimum social safety net and paternalistic ‘welfare state’ to the war-ravaged citizens of Europe and North America. With free state-run healthcare and education, benefits and unemployment payouts, along with government legislation protecting trade union rights in a sort of historic compromise between labour, capital and the state, anarchism began to lose its relevance somewhat in the industrialised economies, with the only real living example of an alternative being the Stalinist bureaucracies of the Eastern Bloc. ‘The European anarchist movement had become so fragmented by the late fifties and sixties that historians of anarchism were sounding its death knell.’ Communism as it was implemented in the USSR had become the most popular and attractive ideology for self-styled revolutionaries, but as people enjoyed the benefits of a post-war boom in welfare-statist mixed economies, as well as the command economies of the East, membership in anarcho-syndicalist unions such as the Industrial Workers of the World slumped and interest in anarchism declined. The Marxist dialectic seemed to have come to a halt – the ‘immiseration of the proletariat’ caused by capitalist competition had not occurred, the cataclysmic world revolution that both the anarchists and socialists had hoped for had not come about, and if anything the masses, particularly in the West, were undergoing a process of ‘bourgeoisification‘. The post-war anarchist Murray Bookchin commends Marx’s First International arch-rival, Bakunin, for accurately prophesying this trend since, ‘he never received the credit due to him for predicting the embourgeoisement of the industrial working class with the development of capitalist industry,’ and rejecting the old idea of the proletariat as the most revolutionary class, instead postulating that the most likely modern revolutionary agitators would be the ‘urban declasses, the rural and urban lumpen elements Marx so heartily despised’ – as New Left thinkers, Marcuse and icons of sixties revolt would also contend. Out of the wilderness of a dying brand of classical anarchist thought, with its focus on workplace organisation and industrial-proletarian revolution, anarchism enjoyed a resurgence in new forms that expressed themselves in the counterculture and youth movements of the sixties, climaxing in the student riots of May 1968 and going on to inspire new waves of activists in latter half of the twentieth century.

Kropotkin’s emotive descriptions of, ‘needy and starving’ workers and, ‘wives and children in rags, living one not knows how till the father’s return’ had less resonance in an age of economic and material prosperity, in which there were echoes of truth – albeit small – in leaders’ self-congratulatory proclamations that we – in generalised terms of wealth – had, ‘never had it so good’. But new patterns in anarchist analysis emerged that expressed an intense dissatisfaction with this prosperous model of advanced consumer-capitalism; the alienation, frustration, apathy, mediation and separation between people that asserted the truism that material wealth, commodities, full employment and high GDP was not correlative to happiness, freedom or well-being. The Situationist International, a collective of avant-garde artists, film-makers, architects and intellectuals, declared that in the present condition of late capitalism, we live in, ‘a world in which the guarantee that we will not die of starvation entails the risk of dying of boredom.’ The classical anarchists and revolutionaries of the nineteenth century had underestimated capitalism’s ability to adapt and survive its cyclical crises of overproduction and underconsumption, and stuck in the dogmatic, doctrinaire models of the old left’s analysis and organisation, they struggled to reach any new conclusions about the nature of contemporary capitalism. The situationists poured equal scorn on leftist ideologues and the bourgeois classes, commenting that, ‘The utter debacle of the left today lies in its failure to notice, let alone understand, the transformation of poverty which is the basic characteristic of life in the highly industrialised countries. Poverty is still conceived in terms of the 19th century proletariat – its brutal struggle to survive in the teeth of exposure, starvation and disease – rather than in terms of the inability to live, the lethargy, the boredom, the isolation, the anguish and the sense of complete meaninglessness which are eating like a cancer through its 20th century counterpart.’ Late capitalism had evolved into a system based on spectacular consumption, a ‘Society of the Spectacle’ in which culture, art and leisure are reduced to commodities and people are reduced to the passive role of spectators. ‘Everything that was directly lived has receded into representation,’ consumption masquerades as participation and alienation, separation and generalised boredom have become the hallmarks of a society in which relations between people are, ‘mediated by images.’ The SI was influenced as much by Nietzschean and individualist philosophical currents as they were by Marx and the classical anarchists. Their scathing rhetoric was reminiscent of Nietzsche’s provocative style and their demand for a society of, ‘masters without slaves’ geared towards the ‘construction of situations’ had echoes of Max Stirner’s anarchist Egoism, which had received criticism from many classical anarchists due to its anti-social thrust but enjoyed a resurgence in post-1945 anarchist movements. However, the situationists retained social and collective elements to their arguments, releasing communiques that demanded the occupation of the factories and, ‘POWER TO THE WORKERS COUNCILS’, and like Bakunin and Goldman before them they expressed their intense hatred of both government and business, stating that, ‘Humanity won’t be happy until the last bureaucrat is hung with the guts of the last capitalist.’ The May 1968 revolts in Paris were the ultimate expression of new anarchist and situationist ideas in practice, and they epitomised a new radical subjectivity that actively rejected the new forms of domination and servitude that encapsulate the condition of humanity in the era of advanced capitalism and remain in place in twenty-first century post-industrial capitalism.

Herbert Marcuse and other neo-Marxists in the Frankfurt School were influential in providing a contemporary critique of traditional Marxism, offering a perspective that was critical of the authoritarian facets of both socialism and capitalist democracy, and contributing an analysis that revealed the totalitarian aspects of modern capitalist democracies, commenting that, ‘Free election of masters does not abolish the masters or the slaves. Free choice among a wide variety of goods and services does not signify freedom if these goods and services sustain social controls over a life of toil and fear – that is, if they sustain alienation.’ Although not decidedly anarchist, Marcuse’s theories exemplified a distrust of authority and an individualistic and libertarian outlook which stemmed from what Althusser would call, ‘the Young Marx’, with its humanistic focus on alienation that complemented the trends in post-war anarchism and had a dramatic influence on the student revolts and countercultural movements of the 1960s as well on left-libertarian activists to this day. Whilst classical anarchists tended to invest their faith in a revolution made ‘by and for’ the proletarians, focusing on a permanent remedy to the antagonism between labour and capital and the emancipation of labour as the ‘great task of the proletariat’, Marcuse and many modern anarchists spurned these notions, pointing out the socially-conservative nature of the post-war proletariat and their deep integration into the capitalist system. The working classes had been fully absorbed into the workings of spectacular commodity-capitalism, and their existence was no longer antagonistic, but rather complementary, to capital. Blurred class distinctions and changes in the dichotomy between bourgeois and proletarian had pacified the traditional working class, producing an army of ‘docile bodies’, to use Foucault’s term, whose (false) consciousness guaranteed an over-identification with their masters and a somewhat contradictory support for the conservation of the status quo. In his work, One Dimensional Man, Marcuse described these vicissitudes: ‘If the worker and his boss enjoy the same television program and visit the same resort places, if the typist is as attractively made up as the daughter of her employer, if the Negro owns a Cadillac, if they all read the same newspaper, then this assimilation indicates not the disappearance of classes, but the extent to which the needs and satisfactions that serve the preservation of the Establishment are shared by the underlying population.’ Like many anarchists after 1945, Marcuse was expressing a desire to move away from what Murray Bookchin called, ‘The Myth of The Proletariat’ and adopt a far more critical position on the essence of the proletariat as a class. Rather than bestowing so-called ‘revolutionary’ notions of ‘class consciousness’ and ‘class unity’ upon workers, they instead recognised that it is this identification with a class and a romanticization of labour that ties the proletariat into the system that dominates them, attaching a certain status to structures which serve to, ”discipline’, ‘unite’ and ‘organize’ the workers, but … do so in a thoroughly bourgeois fashion.’ The revolutionary potential of the worker only increases to the degree that he sheds his, ”class status’ and … class shackles that bind him to all forms of domination.’ The most revolutionary elements of society were the underclasses, the lumpen, the delinquents, those that refuse work and live on the margins, repudiating ‘respectable society’ and refusing social norms, totally disenfranchised, mostly ignoring ‘politics’ and rejecting all forms of authority whether it be the authority of the family, the boss or the police officer. For Bookchin it was people who, ‘smoke pot, fuck off on their jobs, drift into and out of factories, grow long or longish hair, demand more leisure time rather than more pay, steal, harass all authority figures, go on wildcats, and turn on their fellow workers.’ For Marcuse it was, ‘the substratum of the outcasts and outsiders… the unemployed and the unemployable. They exist outside the democratic process… thus their opposition is revolutionary even if their consciousness is not.’

An essential point of divergence between classical anarchist and post-1945 anarchist theory is the refutation of Enlightenment thought by many modern anarchist currents. The classical anarchist tradition was borne out of secular Enlightenment thought, it’s premise being the perfectibility of man and belief in, ‘the ultimate triumph of Reason, Progress and Order.’ This lead to an almost quasi-religious belief in the essential ‘good’ of man, and further to an underlying, semi-teleological idea that humankind would steadily march through history, progressing towards some final ‘end’ – post-revolution – in which man has fully realised his ‘natural’ capacities – which are only denied him by present material conditions – and we will have reached a historical plateau characterised by universal justice, freedom, equality and the perfection of humankind. For the classical anarchists, the state is an artificially-imposed abomination that degrades naturally good human beings. The state and mankind are separate, Manichaean opposites; one essentially good, the other essentially bad. Bakunin asserts that, ‘The State is the most flagrant negation…of humanity’, whilst our ‘humanity’ is defined by natural laws which, ‘are inherent in us, they constitute our nature, our whole being physically, intellectually and morally.’ Influenced by postmodern and poststructuralist rejections of Enlightenment thought, particularly the works of Foucault, the post-anarchists, Todd May and Saul Newman have critiqued Enlightenment ideas from an anarchist perspective, pointing out that the essentialisms and universalities of classical anarchist thinking are simply a reversal of the Hobbessian account the ‘state of nature’, which sees man as innately evil and corrupt and the state as an essential arbiter of anarchic human affairs. Post-anarchists call for the rejection of these classical ‘meta-narratives’, and rather than dismissing anarchism altogether they call for a renewal of anarchist ideas, freeing them from the structures and guarantees that condition and restrict classical anarchism, as well as presenting anarchism as an affirmation, understanding and overcoming of power rather than a total rejection of it. Newman argues that, ‘It is only by affirming power, by acknowledging that we come from the same world as power, not from a ‘natural’ world removed from it, and that we can never be entirely free from relations of power, that one can engage in politically-relevant strategies of resistance against power.’

Some currents of anarchism have strayed even further from their classical predecessors. Post-left anarchy and anarcho-primitivism have attempted to remove anarchism from the confines of ideology and provide a critique of the existing anarchist movements, criticising organisation, morality and sometimes civilisation itself with an absolute rejection of Enlightenment values. Primitivists such as John Zerzan have faced intense criticism from many anarchists for what they see as his regressive vision of utopian society. His advocacy of the destruction of technology, neo-Luddism, and a return to the lifestyle of hunter-gatherers has its source in an all-encompassing critique of modern capitalism and the social ills it creates. For Zerzan, it is a mistake to view technology as a ‘neutral object’ to be used either positively or negatively to serve a specific social function, rather technological advance necessarily leads to alienation and the debasement of human beings. His extreme radicalism and desire for the total break with the status quo is matched by a wish to return to a liberating and more simplistic lifestyle, in which man is at one with himself and with nature, without the constraints of any institution, technology or the disunity and detachment that arises from mechanization, automation and the division of labour. Anti-civilisation critiques begin with the ‘settlement of the land’, the change from hunter-gatherer to farmer and the beginnings of agriculture, described as, ‘the triumph of estrangement and the definite divide between culture and nature and humans from each other… The land itself becomes the instrument of production and the planet’s species its objects.’ Whilst classical anarchism held the sciences, industry and technology in high esteem due to their supposedly liberatory potentials, Zerzan calls for their total annihilation on the basis that from their inception in the Age of Enlightenment and industrialisation, from enclosure and settlement to monetarist capitalism, humanity has only become more enslaved and more detached from the world and themselves with every so-called ‘progress’ and new innovation in the production process.

Post-left anarchists such as Bob Black have called for the abolition of work, whilst Hakim Bey, mixing a strange brand of sufi mysticism and ‘ontological anarchism’, proposes the creation of ‘Temporary Autonomous Zones’ as ‘spaces of resistance’ or ‘spaces of hope’ to remedy the human crises we face in a post-Fordist age. These new brands of anarchism have their roots in the classical works of Bakunin, Kropotkin et al, but their analyses and methods of resistance are very different. The disparities arise because of changes in the nature of capitalism itself and the changes in the relationship between capital, labour and the state that we have witnessed in the last century. Post-war anarchism has also been influenced heavily by more contemporary anti-Enlightenment schools of thought such as postmodernism and poststructuralism, as well as and neo-Marxist and Situationist philosophy, all of which have brought the central libertarian and anti-capitalist tenets of classical anarchists such as Proudhon and Goldman in line with the modern age.